In 1933 the Beech Aircraft Company redesigned its bullish Model 17R biplane into the B17 series that offered performance and economy in a market beginning to emerge from the Great Depression.

In the hot Kansas summer of 1933 Walter Beech was becoming desperate to deliver the first airplane to bear his name. Since its beginning in April 1932, the company’s tiny workforce had built two aircraft – the Beechcraft Model 17R-1 and the nearly identical Model 17R-2. The former was used as a demonstrator and the latter had tentatively been sold to the Loffland Brothers Company in Oklahoma and was scheduled for delivery in June.

As chief engineer Ted Wells struggled to obtain Department of Commerce approval of 17R-2 that summer, it had become painfully obvious to both Beech and Wells that there was little or no market for the two big, fire-breathing Beechcraft biplanes that had been built. During the past 15 months the infant Beech Aircraft Company had gradually become “a starving airplane company,” as Wells described it, and was drawing perilously close to insolvency.

By September 1933, the company had sold one airplane, the 17R-2, and the first ship had yet to find a buyer despite Walter’s best efforts at salesmanship. Although the Model 17R was fast, comfortable and had no equal in its class, the four-place biplane’s price tag of about $18,000 was astronomical and customers were not forthcoming. What Beech needed was a smaller version of the 17R powered by a small static, air-cooled radial engine that would sell for well below $10,000 while matching or exceeding the performance, fuel economy and cabin comfort of competing machines such as the Waco Aircraft Company’s popular cabin biplane series.

With money running out fast and no sales prospects on the horizon, Walter Beech sent Ted Wells and his meager engineering staff back to the drawing board to create a new Beechcraft that would save the company from collapse. Wells had a design in mind and it quickly took shape on paper. Although similar in design to the 17R, the second-generation Beechcraft would be lighter by more than 1,300 pounds and be powered by a seven-cylinder Continental R-670 static, air-cooled radial engine rated at 210 hp. The Continental powerplant consumed fuel at the relatively thrifty rate of 13 gallons per hour at cruise airspeed, compared to more than twice that rate for the nine-cylinder Wright Aeronautical R-975 engine that powered the 17R.

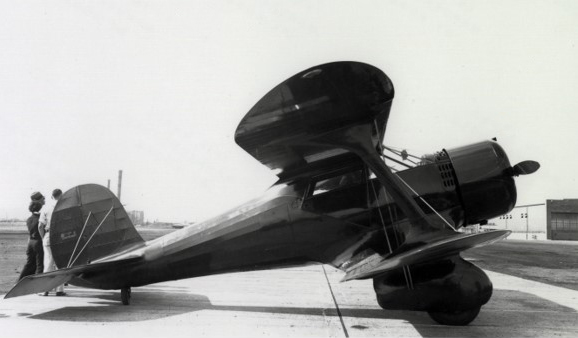

Designated as the Model B17C, the new ship would have a wingspan of 32 feet, a length of 24 5.5 inches and feature a CYH airfoil section developed by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Among the innovative features of the aircraft (for its class) was the fully retractable landing gear operated by compressed air. Beech and Wells considered the retractable gear a necessity if the B17C was to attain its projected maximum speed of 170 mph on a mere 210 hp that made both weight and drag reduction imperative.

Fortunately, the Model 17’s negative-stagger wing configuration provided a convenient, albeit restricted, place to stow the main landing gear (the tailwheel also was retractable). In parallel with development of the B17C, Wells and fellow engineer Jack Wassall were designing a second version of the new aircraft designated B17L. A Jacobs would power it R-755 radial engine rated at 225 hp and offer slightly improved performance.

In January 1934 Beech Aircraft Company applied for an Approved Type Certificate (ATC) for the B17C and B17L. Both ships were essentially identical except for different engines, but the B17L emerged as the more promising design capable of challenging the competition from Waco’s biplanes and monoplanes built by the Stinson Aircraft Company led by Walter’s old friend, “Eddie” Stinson. Although design work on the B17C continued well into 1934 it was eventually abandoned as orders for the B17L outpaced those for its Continental-powered sibling.

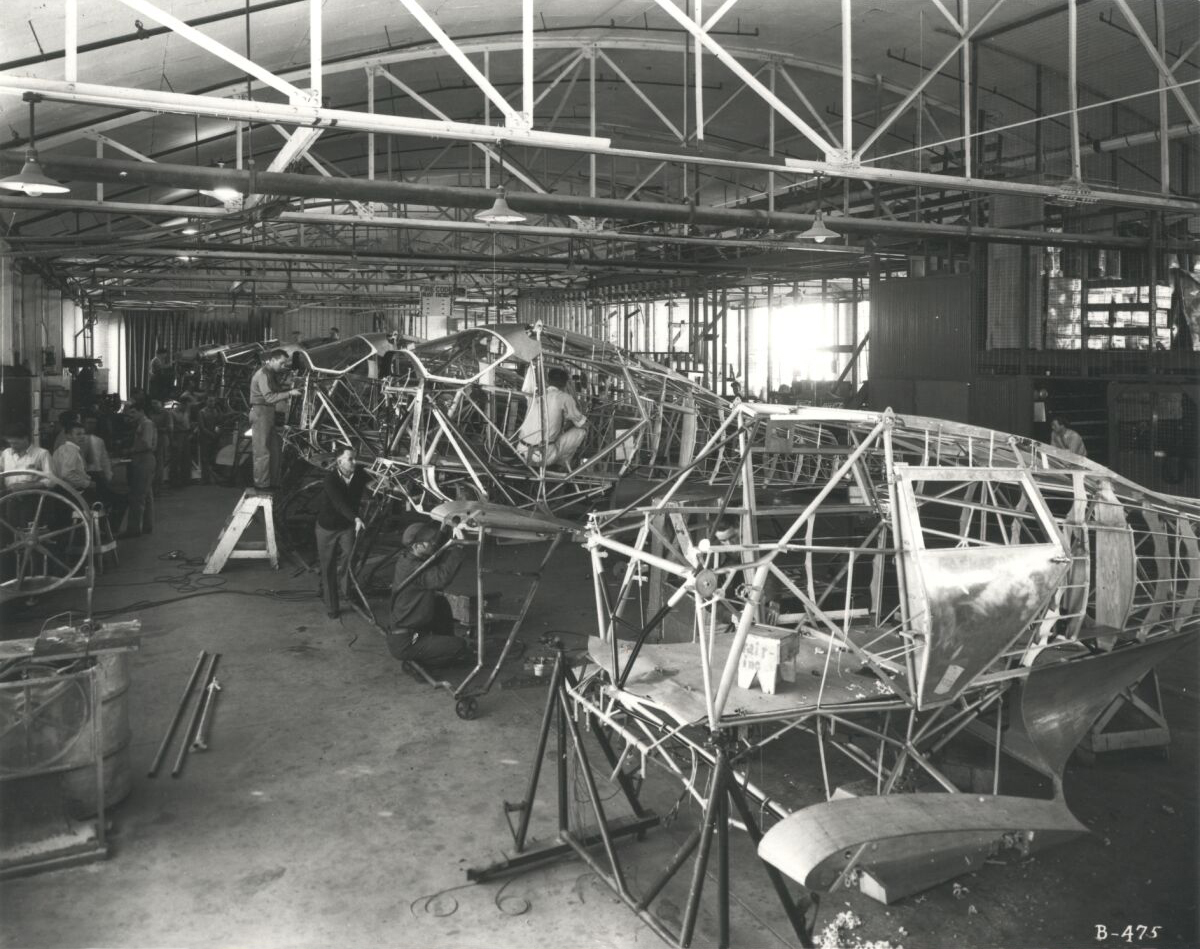

Construction of the first B17L was nearly complete by February 1934. It was the third Beechcraft built and was registered NC270Y. Al Jacobs, president of the Jacobs Aircraft Engine Company in Pottstown, Pa., sent a technician to Wichita with orders to personally supervise installation of the R-755 radial engine. Later that year Jacobs himself visited the Beechcraft facilities nestled in the empty Cessna Aircraft Company factory on Franklin Road.

Jacobs and Walter Beech fully agreed that the market for new airplanes was slowly improving, with Jacobs telling the local press that “aviation manufacturing is at its best since the boom of 1928 and the future looks encouraging.” His team was working three, eight-hour shifts to keep up with demand for the lightweight powerplant, and Beech was adding workers as demand for the B17L continued to grow although the first airplane had yet to be delivered to a customer.

Jacob’s reliable engine, however, had stiff competition from the equally reliable Lycoming R-680 and Continental R-670 that powered other private and business airplanes of the day. The Jacobs had been developed from the LA-2 of 1932, but the more reliable R-755 incorporated enclosed rocker arms for the intake and exhaust valves but retained its predecessor’s archaic battery/coil ignition system instead of magnetos, chiefly to reduce cost.

Here is how that antiquated ignition system worked: A 12-volt lead-acid battery fired one spark plug per cylinder and a six-volt coil fired the second spark plug in each cylinder. Because the B17L’s elementary electrical system was designed for 12-volt DC operation, a dropping resistor was installed to reduce battery voltage at the coil. Although the system was certified it proved less than efficient and was prone to failure of the coil, which reduced ignition to seven spark plugs and resulted in a significant loss of power. In the wake of this weakness, Jacobs developed as 12-volt coil that eliminated the resistor.

After seven months of hard work and many long hours at the drawing board, Wells and Wassall submitted drawings, blueprints and stress analyses for the B17C and B17L to the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce for approval. Meanwhile, on February 27 the first B17L took to the cold, blue skies over Wichita, but by March it was becoming increasingly obvious that the company needed a larger facility to produce the B17 series.

The Cessna factory had served Walter Beech well for nearly two years but the cramped shop space was proving inadequate for even limited production of the new Beechcraft. In addition, Clyde Cessna’s nephew, Dwane Wallace, had plans to reopen his uncle’s factory to build the Cessna C-34 monoplane that had been designed by Wallace and two fellow engineers named Jerry Gerteis and Tom Salter.

A number of cities had attempted to lure the Beech Aircraft Company away from Wichita but Walter and his wife/co-founder Olive Ann had no intention of leaving their prairie homeland. In mid-March 1934 Beech signed a lease with his former employer, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, to use the former Travel Air factory on East Central Avenue as a new base of operations. He planned to complete relocation of the company to its new home in May.

Wells continued to make progress with certification of the B17L. After making a series of technical changes to the design that were mandated by the Aeronautics Branch, engineering inspection and flight tests were authorized. These changes included a redesigned control column, reinforcement of the vertical and horizontal stabilizers; reinforcement of the elevator aft spar; reduced wing rib spacing and redesigned wing attachment fittings for the upper wing panels.

According to Beech Aircraft records, the first 30 B17Ls were equipped with the pneumatically-operated landing gear system that used compressed air, but subsequent airplanes featured an electrically-operated system. Both designs were simple and effective and functioned by controlling the position of the inboard gear strut. By changing position of the strut, the gear could be retracted or extended.

The pneumatic system used an air storage tank, an actuator and a distributing valve that quickly tucked the gear into the wheel wells in a matter of seconds. To retract the gear after takeoff the pilot rotated the latching lever on the instrument panel to the right and pulled it outward – extension required moving the lever to the left, releasing uplock pressure in the system and allowing the gear to partially free-fall into position. Turning a hand crank in the cockpit completed the extension procedure and engaged the downlocks for landing.

In mid-July 1934, the company had delivered two B17Ls and workers were busy fabricating another four that were scheduled for delivery in August. The second airplane built (registered NC12584) was operated by the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company and the third (NC12570) was delivered to the New Jersey Air Service in Atlantic City. Sales accelerated and by September Walter Beech had witnessed the delivery of 11 B17Ls and a steady flow of orders continued for the new Beechcraft.

Almost two years to the day since the first Model 17R-1 had flown, in early November Walter announced that the company’s first large order had arrived – seven airplanes worth more than $60,000—a huge sum at the time. The American Machinery and Foundry Company in New York City had ordered the fleet.

As 1934 drew to a close Beech was enthusiastic about the surge in business and told the local press that the factory was “sold out of production and would be worked at full capacity for at least a month.” The following year would verify his optimism for the future as sales prospects increased. In Beech’s own words, the good times ahead only reinforced his dictum that “introduction of airplanes into business channels offers the only substantial basis” for success.

Beech Aircraft Company had sold 17 airplanes in 1934 with net sales of $173,798 compared with only $17,551 the previous year. The B17L received ATC 560 on December 4 and strong sales clearly indicated that it was the right ship at the right time at the right price. When production of the B17 series ended in 1935, more than 65 airplanes had been manufactured and the reputation of Walter Beech and his airplane company was climbing to new heights.

Back

Back