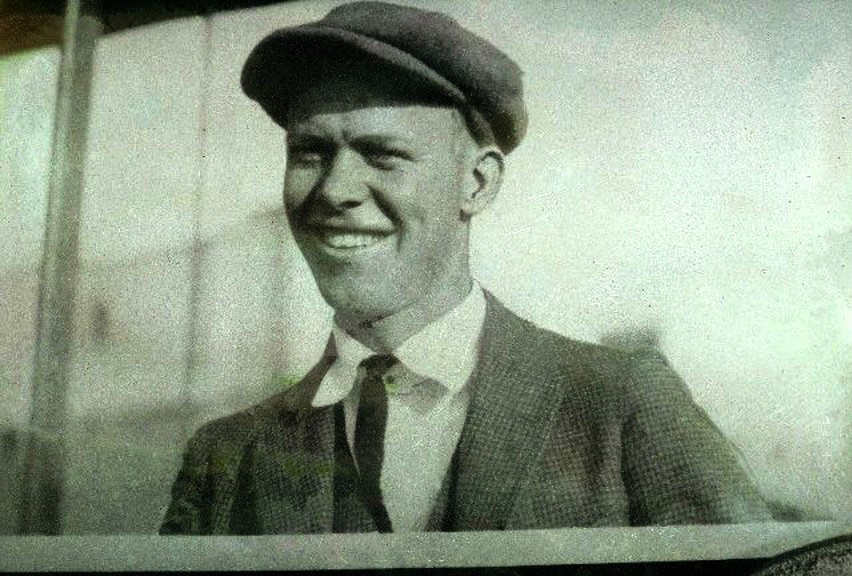

“Matty” Laird’s long and distinguished career designing custom-built biplanes for private and air racing enthusiasts has earned him a place of honor in the annals of American aeronautics.

When Emil Matthew “Matty” Laird left his hometown of Chicago, Ill., and relocated to Wichita, Kan., in 1919, he began the city’s transformation from the “Wheat Capital” to the “Air Capital of the World.” Laird, a self-taught pilot and designer, already had been creating and building airplanes for eight years. His latest creation, a three-place, open cockpit biplane powered by the ubiquitous war-surplus Curtiss OX-5 engine, possessed one important feature – room for two passengers in the front cockpit.

Laird had been wooed away from the “Windy City” by an offer he found too tempting to resist – money and a place to build his airplanes. The invitation had been made by Jacob Melvin Moellendick, a wealthy Kansas oil field tycoon who believed there was not only a potential market for commercial airplanes, but that Wichita was the ideal location for an airplane company.

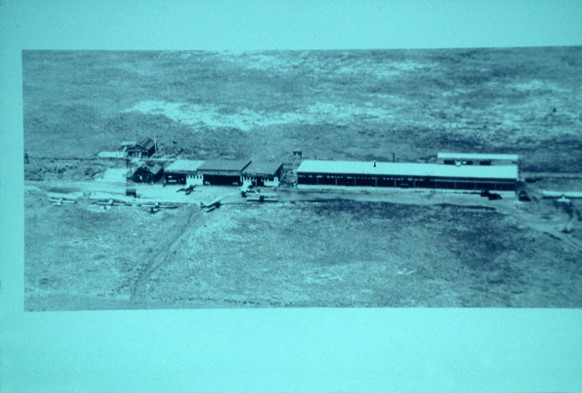

Matty decided the risk was worth the opportunity. Soon after his arrival in Wichita, he was busy setting up shop in an abandoned building in the heart of the prairie city. In addition, he and Moellendick secured land to build another facility at the flying field north of the city. The new airplane was dubbed the “Swallow” and made its first flight in April 1920. It flew well and Laird began preparing for initial production. Within weeks of the flight, news about the Swallow had spread throughout the Midwest and orders from air taxi operators began to arrive at the main office.

By 1920 there was a slow but growing demand for a new commercial airplane. The World War I-era Curtiss JN-4 and other surplus trainers were relatively inexpensive, plentiful and available, but were obsolete before the end of the war. Moellendick and Laird were not the only entrepreneurs to assess the postwar market. There were a large number of small, homegrown companies across the country building new airplanes or modifying war-weary ships for commercial sale. The Laird Swallow, however, represented a bold step in the right direction despite its high price tag of $6,500.

During Matty’s three years in Wichita more than 40 Swallows were built and gave their owners long and reliable service. Although his airplanes were selling well, Matty’s business relationship with Moellendick was gradually eroding and by the autumn of 1923 the situation had become intolerable for Laird. In October he departed Wichita and returned to Chicago where he quickly reestablished himself as a manufacturer of custom-built airplanes.

Early in 1924 the E.M. Laird Airplane Company was doing business in rented facilities near famed Ashburn Field where Laird had spent his early years as a pilot and builder. Matty knew the days of the venerable Swallow were numbered. The trusty biplane was an aging design and could no longer compete in what was rapidly becoming an increasingly competitive marketplace. Matty responded by designing a new ship he called the Laird “Commercial” – a three-place, open cockpit machine powered by an OX-5 engine enclosed in a streamlined, all-metal cowling.

The Commercial was well received by pilots but demand was low, with only a few airplanes built during the next three years. Although Laird’s infant company lost money, sweeping changes soon began to affect the fledgling aviation industry in 1926. Chief among these changes was enactment of the Air Commerce Act. The government recognized that the aviation business had grown to the point that it needed to be regulated. The law required licensing of pilots and mechanics as well as the registration of aircraft. In addition, and of particular interest for financially-strapped manufacturers such as Laird, the Air Commerce Act mandated that all aircraft comply with specific minimum airworthiness standards and receive certification by the federal government.

In May 1927 America’s aviation industry was catapulted to new heights when an obscure air mail pilot named Charles Lindbergh flew a Ryan monoplane across the North Atlantic Ocean to Paris, winning the Orteig Prize and $25,000. “Lucky Lindy” and his “Spirit of St. Louis” had ushered in the dawn of aviation’s “Golden Age.” As with many other small airplane companies, in the wake of Lindbergh’s flight Laird’s business exploded and production increased accordingly.

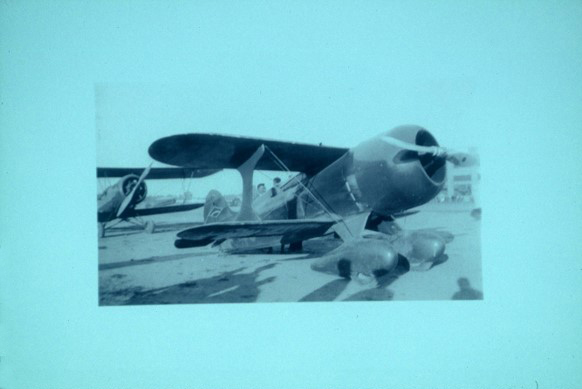

Flying was “all the rage” during the late 1920s and Laird was quick to capitalize on the opportunities it presented. The company introduced new models such as the LC-B and LC-1B, the powerful LC-R and special racing ships, specifically the LC-DW-300 “Solution” that won the 1930 Thompson Trophy Race with “Speed” Holman at the controls. In 1931 Laird’s solid reputation as a builder of racing biplanes led to construction of the powerful LC-DW-500 “Super Solution” that was flown to victory in the Bendix cross-country race by James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle.

The last new designs produced by Laird before the stock market crash of 1929 were designated as the LC-DE. These were smaller airplanes than the LC-B and LC-R but proved to be popular with sportsman and amateur air racing pilots who could still afford to fly. Following the debacle on Wall Street, sales of new airplanes plummeted and the nation fell into the grip of the Great Depression. Many aviation companies closed their doors, but Laird held on by a thread thanks to a few wealthy sportsman pilots who ordered biplanes built to their specific requirements.

In 1931 Matty introduced the LC-EW-450 – a six-place, cabin sesquiplane featuring a first for a Laird design up to that time – an all-metal, semi-monocoque fuselage. Although it was an advanced design with good market potential, the airplane was too expensive for the Great Depression and only one was built. During the 1930s Laird won contracts from American Airlines, TWA, Braniff and United Airlines to repair mechanical components.

Matty, however, never lost his interest in air racing and his thirst for speed. In 1937 he teamed up with flamboyant aviator and air racing pilot, Roscoe Turner. Working in accordance with Roscoe’s instructions, With only a few months before the 1937 National Air Races began in September, Matty and his team completely rebuilt Turner’s wrecked Wedell-Williams Model 44 racer and a new, untested monoplane dubbed the “Turner Special.” It was powered by a 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney “Hornet” radial engine rated at a bellowing 1,000 hp. Upon completion of the racer Laird designated it the LTR-14 (LTR for “Laird/Turner Racer”).

In 1934 Turner had won fame by winning the Thompson Trophy Race in his Wedell-William’s monoplane and planned to win again in 1937 with the new LTR-14. Unfortunately, he placed third in that event and later listed Laird’s work on the airplane’s fuel tank among the reasons for his failure to win.

Roscoe had promised Matty that he would use the money he hoped to win from the Thompson Trophy and the cross-country Bendix races to pay for work done on the two air racing ships. Matty was reluctant to accept Turner’s promise but relented and agreed to wait for payment. According to Laird’s daughter, Joan Laird Post, Turner never paid the debt he owed her father, and the two men parted company.

Roscoe and the LTR-14 went on to win the 1938 and 1939 Thompson races. Turner became the only pilot to claim three victories and was given permanent possession of the Thompson Trophy. Laird, however, was not given any credit publicly for his work on the airplane. As a final insult, the Laird company logo was removed from the LTR-14’s vertical stabilizer.

During World War Two E.M. Laird worked as an engineer for the LaPorte Corporation that built tail sections for the Martin B-26 medium bomber as well as airframe assemblies for the Consolidated B-24. After the war Laird considered building a four-place, high wing monoplane but decided against the plan, and in 1945 his 30-year involvement in aviation ended.

E.M. Laird died in 1982. He left behind a legacy of speed and a reputation for building superior custom airplanes that earned the respect of both customers and competitors. Above all, the self-taught pilot and designer from Chicago had earned the right to be called one of America’s genuinely great aviation pioneers and a major contributor to Wichita’s fame as the “Air Capital of the World.”

Back

Back