Lloyd C. Stearman ranks as one of America’s greatest aviation personalities and the airplanes he designed earned a worldwide reputation for performance and reliability.

After a stunning career in aviation that spanned more than 50 years, Lloyd C. Stearman lost his battle with cancer on April 3, 1975. During his funeral at the National Sawtelle Cemetery in California, mourners heard eulogies to the man who began his involvement with the fledgling aeronautics industry in 1919 and never looked back.

The first airplane he saw was flown by none other than Clyde V. Cessna – a former car salesman from Enid, Oklahoma, turned intrepid aviator. Stearman began his aviation career under the supervision of another pioneer airman – E.M. “Matty “ Laird, who had moved from his home in Chicago to Wichita, Kansas, to form the E.M. Laird Company Partnership with businessman Jacob “Jake” Moellendick. That move would eventually transform the “Wheat Capital of the World” into the “Air Capital of the World,” and Lloyd Stearman would play a leading role in that unfolding story.

Aviation, however, was not Stearman’s initial choice as a vocation. Instead, Lloyd set his sights on becoming a civil engineer and in 1917 he enrolled at Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan, Kansas. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Lloyd responded to the call to arms and enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

He was chosen for flight training and eventually soloed in a Curtiss N-9 floatplane at Naval Air Station North Island near San Diego, California. Although the war ended before Stearman could earn his wings, he did qualify as a Master Airplane Rigger in the United States Navy Reserve Flying Corps.

With the “War to end All Wars” over at last, Lloyd returned to his hometown of Harper, Kansas, and pondered his future. In 1919 he accepted a job with the S.S. Voight company in Wichita where he worked as a journeyman architect and draftsman. One day he read an advertisement calling for workers to build the “Swallow” biplane at “Matty” Laird’s company. Stearman jumped at the opportunity to enter the aviation business and was soon busy building Swallows and helping Laird with engineering tasks. Lloyd’s engineering background and drafting abilities were put to good use around the factory, and he was soon supervising workers.

In the autumn of 1923 Laird resigned from the company and returned to Chicago. Three years of growing distrust and heated disagreements with the headstrong Moellendick had taken their toll, and Matty knew it was time to leave. Jake promoted Stearman to chief engineer. His chief task was to design a replacement for the Swallow.

Dubbed the “New Swallow,” the biplane first flew in December 1923 and was hailed as a major innovation by pilots. Stearman, with input from co-worker and factory manager Walter H. Beech, incorporated a number of technical and aerodynamic improvements into the aircraft, such as a metal cowling around the 90-hp Curtiss OX-5 engine, a reserve fuel tank and a new landing gear arrangement.

The New Swallow was an immediate success. Not only was the airplane heralded by pilots and the press as a significant step forward for commercial aviation, it lifted Lloyd Stearman’s name into the national spotlight for the first time. In 1924 Stearman was ready to take the New Swallow to the next level technically – replace the wood fuselage structure with welded steel tubing. Beech agreed, but Jake rejected the idea and forbid any changes.

Stung by Moellendick’s intransigence, Stearman and Beech made a bold move – they resigned and, in partnership with Clyde V. Cessna and an elite group of Wichita businessmen, founded the Travel Air Manufacturing Company late in 1924. Stearman already had a new design ready for manufacture. Known as the Model “A” it was essentially an upgraded version of the New Swallow, but incorporated the welded steel tube structure favored by Stearman and Beech.

During the next two years Stearman designed a series of biplanes for the company and engineered the Model “A” to accept installation of the new J-4 nine-cylinder, static air-cooled radial engine built by the Wright Aeronautical Company. Known as the Model BW, the new Travel Air was the first of a family of radial engine-powered airplanes to roll of the production line. Travel Air soon became a major force in the infant commercial airplane business, and the combination of Lloyd Stearman’s design prowess and Walter Beech’s salesmanship were chiefly responsible for the rapid growth of the company.

Stearman, however, was becoming restless and looked westward to California for his next challenge. In the autumn of 1926 he resigned from Travel Air and, in partnership with aviator Fred Day Hoyt and businessman George Lyle, formed Stearman Aircraft, Inc., located at famed Clover Field in Santa Monica. Hoyt, a well-known stunt pilot for Hollywood’s movie industry, had convinced Lloyd that they could sell airplanes to wealthy thespians and to operators of the growing contract air mail business. It was an opportunity for Stearman to operate his own airplane company and he agreed to the proposal.

A small building in nearby Venice was used to fabricate airplanes with final assembly and flight testing accomplished at Hoyt’s facility on Clover Field. Stearman’s latest design and the first to bear his name was the C1. Completed in March 1927, it was an elegant biplane featuring aesthetic appeal from spinner to rudder. Powered by the ubiquitous Curtiss OX-5 engine, the C1 accommodated a pilot in the aft cockpit and two passengers or mail in the front cockpit.

The C1 was followed by the C2 and later the C2M powered by a Wright J-4 radial engine. The J-4 was a perfect match for the C2M’s rugged airframe. Stearman had been quick to realize that static radial engines were the wave of the future for commercial and military aviation, and designed the C2M’s airframe to accept a radial engine. Although the Curtiss engine was cheap and available in large numbers as war surplus equipment, by 1927 it was obsolete.

In May of that year Lindbergh’s nonstop flight to Paris demonstrated emphatically the technical superiority and reliability of radial engines. In defense of the OX-5, however, it must be said that the Curtiss V8 powerplant was chiefly responsible for the genesis and growth of the infant American commercial aviation industry after World War I.

The C2M was among the first airplanes specifically designed to meet the demanding requirements of air mail operators. It could carry up to 400 pounds of mail and was capable of flying about 500 miles at a cruising speed of 110 mph. Lloyd’s first customer was Varney Air Lines that put the C2Minto service in late summer 1927.

After less than one year of operation, Stearman Aircraft, Inc., faced a growing list of orders for new airplanes but lacked insufficient capital and facilities to build them. Lloyd and his associates hoped that a group of California businessmen would come to their rescue. Instead, it was a group of Wichita businessmen and old friends of Lloyd Stearman that made him an offer he could not refuse – relocate to Wichita. Led by Walter P. Innes, Jr., the group raised more than $60,000 in only a few days and convinced Lloyd that the future of Stearman Aircraft, Inc., was in Kansas, not California.

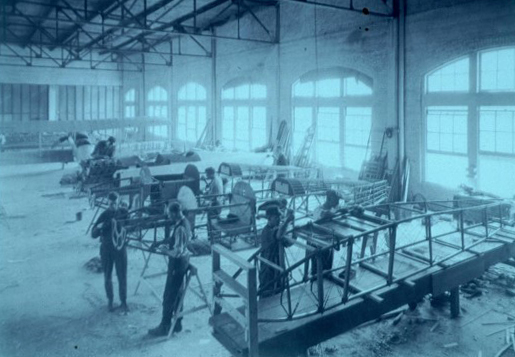

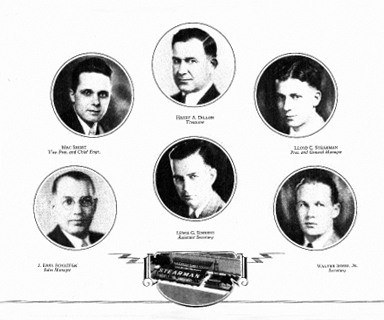

Lloyd liked the West Coast and had made many friends there, but he took the offer and made the trip eastward to Kansas. In October 1927 the renamed Stearman Aircraft Company resumed operations in a vacant railroad car factory five miles north of the city. Allied with his close friend and fellow engineer Mac Van Fleet Short, who had joined the company in Santa Monica, Lloyd designed improved biplanes such as the C2B, C3B and the larger M-2 “Speed Mail” aimed at the air mail industry.

Thanks to “flying fever” that struck America in the wake of Lindbergh’s epic flight across the Atlantic Ocean, in 1928 sales were brisk and the factory was operating two shifts to keep pace with demand. Stearman’s bread-and-butter product, the C3B, was popular with sportsman pilots and businessmen, and in mid-1929 the company introduced its C3R “Business Speedster” powered by a Wright J6-7 radial engine. In addition, the LT-1 cabin biplane made its debut. Built as a derivative of the M-2, the LT-1 carried four passengers in a forward cabin and nearly 1,000 pounds of mail.

To fill a gap in the Stearman product line, Stearman and Mac Short had designed an intermediate class biplane designated the Model 4 series. It was smaller than the M-2 and LT-1 but larger than the C3R and was well suited for a variety of missions. The Model 4 entered production in the fateful month of October 1929 and proved popular with air mail contractors, wealthy sportsman pilots, oil companies and the airlines, remaining in production into the early 1930s.

In 1929 Wall Street was enjoying unprecedented success although the signs of disaster were clearly visible but went unheeded. Among the targets for takeovers and acquisitions were airplane companies and the highly successful Stearman Aircraft Company was no exception. Wichita was living up to its reputation as the “Air Capital of the World” and in 1928 the Stearman Aircraft, Travel Air and Cessna Aircraft companies had built more than 900 airplanes and forecast twice that number for 1929.

A number of investor groups approached Lloyd Stearman about acquiring his company but their offers were quickly rejected. But in July the giant United Aircraft & Transport Corporation (UATC) succeeded where others had failed. UATC added the Stearman Aircraft Company to its conglomerate that already included the Boeing Airplane Company, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft, Chance-Vought Corporation, Hamilton Aero Manufacturing Company and Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation.

As the summer of 1929 faded into autumn, Wall Street was teetering on the brink of disaster. As early as March a series of tremors had shaken the stock market and by September the Federal Reserve Board feared collapse was imminent. On October 29 the day of reckoning finally arrived and “Black Tuesday” became a phrase forever associated with financial disaster. The market had crashed, and aviation was among its earliest victims.

By late 1929 sales had slowed and Lloyd Stearman was forced to begin trimming the company’s workforce. It was clear that the commercial market for airplanes was drying up fast, and the board of directors turned their attention to other opportunities including airline and military contracts. As for officials of UATC, they were reeling from the effects of October 29 but were determined to hold their shaky conglomerate together and weather the economic storm. Fortunately for the Stearman Aircraft Company, they succeeded.

Although Lloyd Stearman recognized that being a cog in the corporate wheel of the UATC machine had its business advantages, he was becoming restless once again to strike out on his own. He was not happy being a manager – he was a designer, an engineer and an innovator. Despite his growing discontent with UATC and its management practices, Lloyd designed the Model 6 “Cloudboy” – a utilitarian, spartan biplane intended to be the company’s entry-level product.

Powered by small radial engines in the 150-300-hp class, the Model 6 held promise as a primary trainer for the military, particularly the U.S. Army Air Corps that was seeking proposals for a new primary trainer to replace the aging Consolidated PT-3. First flown in the summer of 1930, the “Cloudboy” was modified to meet military requirements and designated XPT-912 and YPT-9 by the Army. Unfortunately, the YPT-9 was rejected in favor of the Consolidated YPT-11. Only 10 “Cloudboys” were built, and all were sold to commercial customers.

The company, however, lost more than a military contract, it lost Lloyd Stearman. In July 1931 he resigned. It was time to move on to other challenges and in October he and his family moved back to California. Lloyd joined forces with his old friend and loyal customer Walter T. Varney and businessman Robert E. Gross to form the Stearman-Varney Aircraft Company. It was an unlikely venture given the Great Depression’s tightening grip on America. The trio acquired the assets of the Lockheed Aircraft Company, a division of the defunct Detroit Aircraft Corporation, for a mere $40,000.

Always looking forward, during the summer of 1931 Stearman had been working on the design of a revolutionary, all-metal cabin monoplane. It would evolve into the Lockheed Model 10 “Electra” that first flew early in 1934 and represented the future of commercial aviation in the United States.

With Lloyd Stearman’s departure the Stearman Aircraft Company struggled to keep its doors open, chiefly by building components for the new Boeing Model 247 and refurbishing Boeing Model 40 air mail biplanes that were being retired in favor of all-metal monoplanes such as Jack Northrop’s innovative “Alpha” and Boeing’s evolutionary “Monomail.”

The company was led by Julius E. Schaefer, a former Army aviator and successful automobile salesman who had joined Stearman Aircraft in 1928 and was appointed president in September 1933. Schaefer was a talented marketer and played a major role in driving sales upward during the company’s glory days of 1928-1929. By 1933, with the commercial airplane market still in shambles, he had decided that the company would focus on military contracts.

Mac Short and his team of engineers were assigned the task of designing a new primary trainer that would attract the attention of the Army Air Corps and the U.S. Navy. Based on a preliminary drawing of a modified “Cloudboy” completed by Lloyd Stearman in 1931, the team modified the design into the Model 70. The sole prototype flew in January 1934 with company test pilot “Deed” Levy at the controls.

The airplane was evaluated at Wright Field by Army pilots and at Naval Air Station Anacostia near Washington, D.C. Both Army and Navy aviators were impressed with the biplane’s overall handling and flight characteristics, but no orders were forthcoming until May 1934 when the Navy ordered a modified version designated NS-1 (Stearman Model 73). The order for 41 airplanes was a major victory for Schaefer and the company (the Model 73 later evolved into the N2S series).

As workers toiled to build and deliver the first NS-1 trainers, the Stearman Aircraft Company came under the supervision of the Boeing Aircraft Company and increased efforts to win orders from the Army Air Corps. The Model 73 was upgraded to the Model 75 and in 1935 the Army ordered 20 airplanes designated PT-13, powered by a nine-cylinder Lycoming radial engine rated at 225 hp. The two contracts were worth more than $400,000 and Schaefer scrambled to hire and train workers to complete the airplanes on schedule.

The orders were part of a modernization program by the Army and Navy to upgrade their aviation fleets after years of neglect by a spendthrift Congress. With Adolph Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and Japan’s ongoing, aggressive war against China threatening world peace, President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew America had to begin rearming and reequipping its military forces in preparation for a potential war on two fronts.

In addition, the Great Depression, which had inflicted devastating economic harm upon the United States for nearly five years, was finally beginning to weaken by 1935 and the nation slowly realized that “happy days are here again.”

Fortunately for Schaefer and his workforce, in 1935 the Army Air Corps established the General Headquarters Air Force, a combat air organization that evolved into the Air Force Combat Command (AFCC). Its chief purpose was to develop and test aerial strategic and tactical doctrines upon which an “air war” would be fought. An integral part of the AFCC was the Materiel Division that focused on the massive task of training thousands of young men to fly bombers, fighters and transports. The Materiel Division created training facilities and from these grew the continental commands of the Army Air Forces that were chiefly responsible for building a modernized air force into the fighting machine it became during World War II.

Through 1936-1937 more contracts for primary trainers, as well as fabrication of components for Boeing’s new “Flying Fortress” heavy bomber, kept fattening the company’s order books. Hundreds of workers were hired and the factory was completing a new trainer every day, and every few days Army and Navy pilots were flying them away to Randolph Field in Texas and Pensacola in Florida.

In April 1938 the Stearman company was renamed the Stearman Division of Boeing. Schaefer remained at the helm as first vice president under Boeing president Clairmont L. Egtvedt. As 1938 gave way to 1939 war clouds were gathering over Europe and diplomatic tensions between Washington and Tokyo were increasingly strained. In response, America stepped up its war preparations and the economy boomed to unprecedented height as millions of men and women went to work creating President Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy.”

The Stearman Division, already hard pressed to keep up with skyrocketing demand for new trainers from the Army and Navy, in June 1940 received more orders for hundreds of additional PT-13, PT-17 and N2S aircraft. The factory underwent multiple expansions to accommodate increased production rates, and by September 1,400 employees were on the payroll working three, eight-hour shifts six days a week, and completing a new trainer every three hours.

In the months ahead Stearman factory was buzzing with activity. Production was reaching a frenetic pace and the workforce had increased to more than 3,000 by April 1941. A milestone was reached in March 1941 when the Army and Navy accepted the 1,000th and 1,001st primary trainers built since the national defense program began in 1939. Only five months later the 2,000th trainer rolled off the assembly lines.

Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December threw the entire United States military/industrial complex into overdrive. Although the hardware of war was being manufactured at unheard of rates, the training of pilots fell far short of requirements. In the wake of that shortfall, orders for thousands of primary trainers were placed with the Stearman Division. During 1942-1943 the excruciating pace of production left no time for celebration at the factory when the 3,000th, 4,000th, 5,000th and 6,000th Stearman trainers were completed and quickly ferried to their bases of operation.

In April 1943 production reached 275 airplanes, among them the 7,000th trainer built by the division. The seemingly overwhelming challenge to build more and more airplanes each month had been met by Stearman employees, and the military services had used those airplanes to good effect. From July 1939 to August 1945, the Army Air Forces graduated 768,991 pilots. Of these, 233,198 completed primary training and a majority of them earned their wings flying a PT-13 or N2S.

When the war ended in August 1945, Boeing Aircraft Company’s Wichita Division (which included the Stearman facilities), along with the Cessna Aircraft Company, Beech Aircraft Corporation and the Culver Aircraft Company, had manufactured more than 25,800 aircraft plus spares to build another 5,000. Of that total, the Stearman factory had built 8,584 primary trainers or about 44% of all primary training aircraft built during the war.

As demand for PT-13, PT-17 and N2S trainers increased during the war years, production peaked in April 1943 when nine airplanes were completed every working day. By contrast, thanks to increasingly efficient manufacturing procedures, the hours required to produce one airplane was reduced to 878 in July 1943 from a high of 2,512 in April 1940.

Boeing’s Wichita manufacturing juggernaut also produced 1,644 B-29 heavy bombers during the war, eventually reaching an astounding production rate of 4.2 bombers per work day for an average of 100 airplanes per month – a remarkable testimony to America’s industrial power that neither Germany or Japan could hope to match.

In a further testimony to generations of Stearman workers, from 1927 to 1962 they built more than 14,500 aircraft including 247 biplanes, 10,346 primary trainers (including spares), assemblies for 750 Waco CG-4A assault gliders, 1,769 B-29 heavy bombers (including spares), 12 single-engine L-15 liaison airplanes, 1,390 B-47 “Stratojet” medium bombers and 467 B-52 “Stratofortress” bombers.

Their impressive accomplishments were a testimony to the dedication of the American worker, to Wichita’s workforce, and to a Kansan named Lloyd C. Stearman and the company that bore his name.

Note: For those interested in reading more about the background of Lloyd C. Stearman and the history of the Stearman company and its airplanes, we suggest “Stearman Aircraft – A Detailed History.” Available from Specialty Press at www.specialtypress.com.

Back

Back