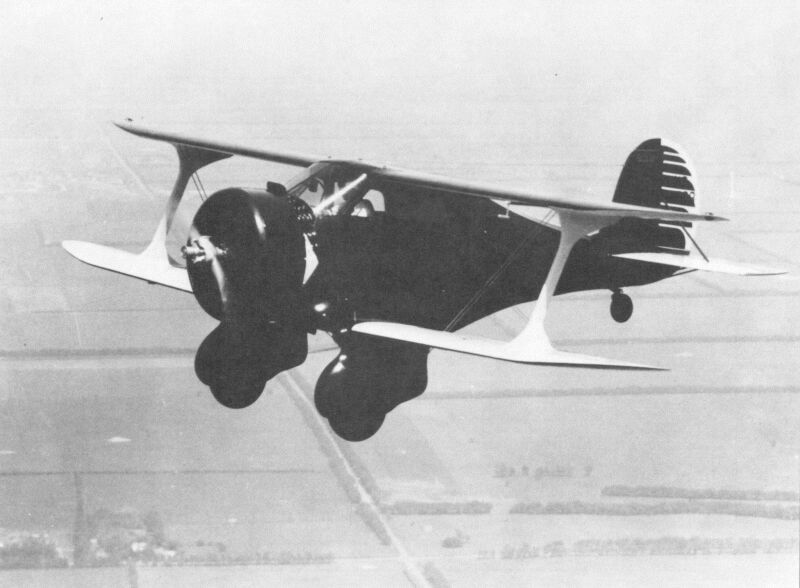

The Model A17F and A17FS were like no other Beechcrafts ever built – powerful, brutish biplanes whose high performance was nothing short of spectacular for their time.

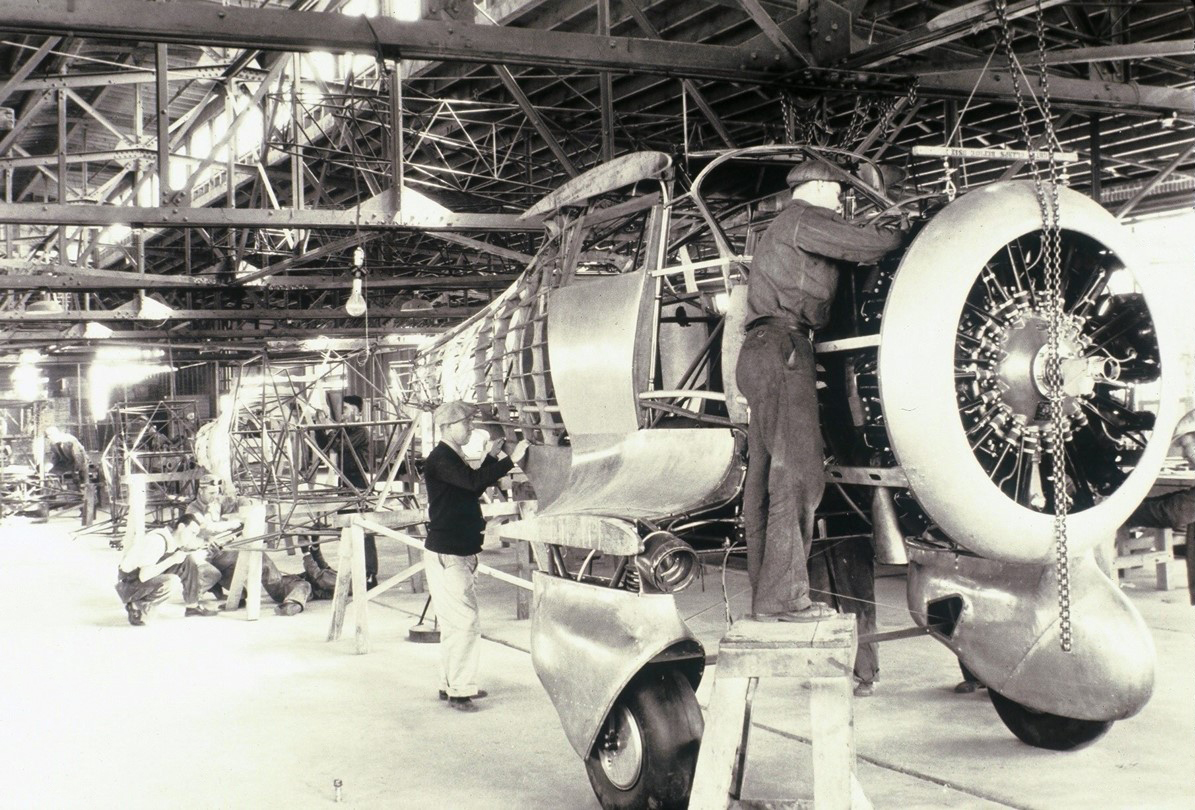

As 1933 drew to a close Walter Beech and his infant airplane company had sold one airplane – the second Model 17R built—and had orders in hand for two additional aircraft. Unlike the first Beechcraft, however, these two machines were to be powered by muscular nine-cylinder Wright “Cyclone” radial engines. The first, dubbed the Model A17F, mounted an R-1820F11 rated at 690 hp while the second ship was equipped with a supercharged SR-1820F3 that produced 710 hp.

The A17F had been ordered by the Goodall-Worsted/Sanford Mills company to fly officials to various clothing factories operating in several states. The second ship was designed specifically to compete in the MacRobertson International Trophy Race scheduled for 1934. The grueling, 12,000-mile route would begin at London and end at Melbourne, Australia.

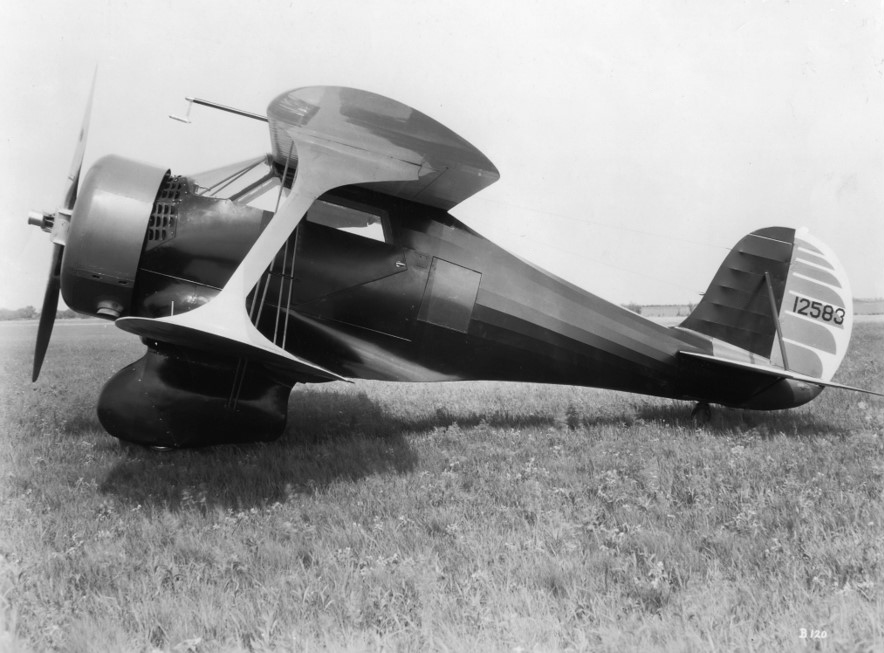

Beech Aircraft Company completed the A17F in May 1934. It was the ultimate single-engine, four-place business airplane of the mid-1930s and could attain a maximum speed approaching 220 mph – a speed that placed it in the same class with only a few Army Air Corps military pursuits of the day. To feed the thirsty Cyclone powerplant the A17F’s fuel tanks held 155 gallons. First flown early in May 1934, the A17F was delivered to Goodall-Worsted pilot Robert Fogg on May 27.

The airplane’s interior was plush, outfitted with Goodall-Worsted velour and mohair fabrics made by Sanford Mills especially for the Beechcraft. As a final custom touch, the company had the Beech factory paint the words “Tailored By Goodall From the Genuine Cloth” on both sides of the aft fuselage. Priced at $24,500, the bullish biplane was resplendent in its glossy black and red paint scheme trimmed in cream to match the interior. As the A17F departed that day from the old Travel Airfield in East Wichita, Fogg knew he was flying one of the world’s fastest biplanes, and speed was its most salient characteristic.

As Fogg flew eastward to the company’s headquarters in New England, the big Beechcraft drew attention wherever it landed for fuel. After arriving in Boston late that day, Fogg wired Walter Beech expressing his admiration for the mighty A17F – “Breakfast in Wichita, dinner in Boston and headwinds all the way. Congratulations on your latest masterpiece – the world’s finest aircraft. Progress demands creation rather than imitation, and you have achieved it again.” Despite Fogg’s praise for the speedy ship, after only one year in reliable service to the company the vagaries of an economic depression forced Goodall-Worsted to sell the A17F to the Hughes Tool Company.

The ship was later bought by race pilot Robert Perlick and prepared for competition in the 1937 Bendix Trophy race. Unfortunately, during the takeoff roll the heavy weight of fuel caused the landing gear to collapse and Perlick was out of the race. He tried again in 1938 and was poised to win the event when the Cyclone engine went silent due to fuel starvation. To add insult to injury, in 1944 the Beechcraft met its end in a hangar fire.

As for the A17F’s more powerful brother, the A17FS, its career was short-lived and uneventful. The airplane was completed too late to enter the MacRobertson race. The many promises of support and money made by Wichita businessmen and other people were not forthcoming and the situation was further compounded by the high cost of shipping the biplane to England. Louise Thaden, who was chosen to pilot the A17FS on its epic journey, estimated it would cost $8,000 alone to transport the Beechcraft to London.

Walter Beech had an expensive “hangar queen” on his hands and with his hopes of race glory dashed he began a vigorous campaign to sell the airplane. As the weeks passed Walter grew increasingly irritated. Despite his sales efforts no buyers stepped forward to acquire the massive A17FS. In 1935 Walter finally found a buyer – the United States government’s Bureau of Air Commerce. The agency planned to have aviation inspectors fly the ship on inspection tours around the country.

After a series of modifications demanded by the Bureau, Beech Aircraft Company finally delivered the aircraft in July 1935 but flew it only about one year before because of the high operating costs and frequent repairs needed to keep it airworthy. These issues, coupled with the availability of new, more modern and fuel-efficient airplanes led the Bureau to strike the A17FS from its fleet inventory in August 1936. Walter Beech bought back the ship and in August it was retrieved from a hangar at a Cincinnati, Ohio, airport where it had been in storage since June. Its exact fate remains a mystery, although rumors persisted for years that Walter eventually resold the airplane to a buyer in California. Another possibility is that Beech had the aircraft dismantled and destroyed.

The A17F and A17FS were unique airplanes, not only as Beechcrafts but as handcrafted flying machines built in a dying era when steel tubing and fabric were being overtaken by all-metal aircraft. It is certain, however, that the bullish Beechcrafts would never be forgotten. They appeared on the aviation scene only briefly, yet they made a lasting impression on those pilots who experienced the sheer thrill of flying an airplane that had no equal.

Back

Back